In my earliest memory, my grandfather is bald as a stone and he takes me to see the tigers. He puts on his hat, his big-buttoned raincoat, and I wear my lacquered shoes and velvet dress. It is autumn, and I am four years old.

Among all the books I've read in 2011, Téa Obreht's stunning début novel The Tiger's Wife (2011) is undoubtedly the one that caught my attention the most, and I'm happy to close the year 2011 (er… with a bit of a delay) reviewing it. Not only is Obreht gifted with words but her novel is so different from any other novel I've read that it made the reading experience all the more refreshing.

Set in an unnamed Balkan province, the novel relates the journey Natalia Stefanovic, a young doctor, embarks on after the death of her beloved grandfather. Going from city to city for professional reasons or in order to get her grandfather's personal belongings back, she goes back in time and tries to piece together elements of his life by recalling the extraordinary stories he used to tell her when she was a little girl.

There is such a strong episodic quality to Obreht's novel that makes it stand out from other contemporary works of fiction and tells us a lot about the author's experience with short stories. The Tiger's Wife is a celebration of storytelling. Folk tales spread on the pages like a mural painting that survived the wars and reveals to us characters coming to life. Natalia, the narrator, comes to realise that her grandfather's tales about the deathless man, the tiger's wife, the butcher's son Luka or Darisa the bear were not the fruit of his imagination but real stories that shaped his life and will, in turn, shape hers.

Throughout the book, we learn about the grandfather's encounters with the deathless man, a young immortal man who can predict the death of someone with a magic coffee cup; we learn how the arrival of a tiger in Galina (the grandfather's birthplace) changed the life of the villagers; we learn how Luka ended up marrying the sister of his bride: “he lifted the veil in the ceremonial gesture of seeing his wife for the first time and found himself looking, with almost profane stupidity, into the face of a stranger.”

What amazes me in Obreht's book is how these tales, full of exoticism and reflecting the richness of Balkan folklore, intertwine realism and fantasy and how, despite this, we still want to believe in them. Natalia, from now on the guardian of these mythical tales, recounts how Gavran Gailé – the deathless man – proved his immorality by going into a lake “with weights tied to [his] feet”: “And there he is, […] climbing slowly and wetly out of the lake on the opposite side, […] and it's been hours.”

Of course, we know that when stories are passed from one person to another they may undergo change. We also know that sometimes memory gaps occur and elements are left out, or that when telling a story some things are mixed up, remain untold or just cannot be explained. But despite all this, there is something inherently truthful in The Tiger's Wife and in these human stories worthy of the fireside.

Of course, we know that when stories are passed from one person to another they may undergo change. We also know that sometimes memory gaps occur and elements are left out, or that when telling a story some things are mixed up, remain untold or just cannot be explained. But despite all this, there is something inherently truthful in The Tiger's Wife and in these human stories worthy of the fireside.

Quote from the book:

“Young boys are fascinated with animals, but for Darisa the hysterical dream of the golden labyrinth, coupled with the silent sanctuary of the trophy room, amounted to a much simpler notion: absence, solitude, and then, at the end of it all, Death in thousands of forms, standing in that hall with frankness and clarity—Death had size and color and shape, texture and grace. There was something concrete to it. In that room, Death had come and gone, swept by, and left behind a mirage of life—it was possible, he realized, to find life in Death.”

About the publication: Random House (USA), 2011.

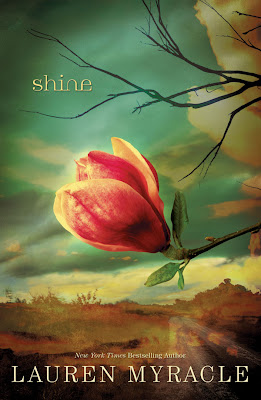

About the cover design: Anna Bauer.